DID LES MISÉRABLES JUST WIN OVER THE FRENCH?

How Théâtre du Châtelet's new production in Paris has rehabilitated the megahit musical's hometown reputation, and where the show goes next

Welcome to your weekly guide to the global theater industry. New to Jaques? Check out this handy explainer.

“Do You Hear the People Sing?” becomes “By the will of the people” (“À la volonté du peuple”). “One Day More” is “The big day” (“Le grand jour”). And instead of fantasizing about a “Castle on a Cloud,” young Cosette dreams of a doll in a shop window (“Une poupée dans la vitrine”).

Did I spend my adolescence listening to the original Broadway cast recording of Les Misérables over and over again until those double cassettes unspooled from exhaustion? I sure did—and the fact that I carry every single English-language lyric of that show in my bones made seeing the musical in French last month, at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, a doubly fascinating experience.

In addition to clocking all the ways this new version differentiates itself from the original West End staging, you can also listen for all the moments when the revised French-language adaptation diverges from the English and watch out for how that colors the storytelling. (There are English supertitles for those whose high school French is rusty.) When it’s all over, you can walk out of the Châtelet and look across the Seine to the newly reopened Notre Dame.

I’d recommend it—but good luck getting a ticket. Because in a startling reversal of fortune, this new Parisian production of Les Miz is… actually really popular?

Although it’s best known in the English language version that became a global megahit, Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s musical adaptation of Les Misérables was initially written in French. The story, as I’d always understood it, was that upon its premiere in Paris in 1980, Les Miz instantly flopped, and it’s been unpopular in France ever since. That’s not quite true—more on that in a moment—but it’s certainly the case that ever since producer Cameron Mackintosh turned the show into a West End and Broadway blockbuster, France has been almost the only place on Earth that hasn’t embraced it with open arms.

The Châtelet’s new production seems to have turned the tide. The extremely limited run (Nov. 20-Dec. 31) is essentially sold out, and plans are being hatched for a potential future life in France and around the world. While there were plenty of international visitors at the performance I saw, there seemed to be just as many local, French theatergoers cheering just as enthusiastically.

A big part of the excitement stems from the production’s homegrown take, which aims to more closely match the textures of Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel—a literary masterpiece for which the French feel a great deal of cultural ownership and pride. It helps, too, that this Les Misérables arrives at a moment when Paris seems to have finally come around to embracing musical theater in general.

In this SPOTLIGHT STORY, I’ll highlight

the ups and downs—and ups again—of Les Misérables in Paris,

how this new version came to be and the intentions behind it,

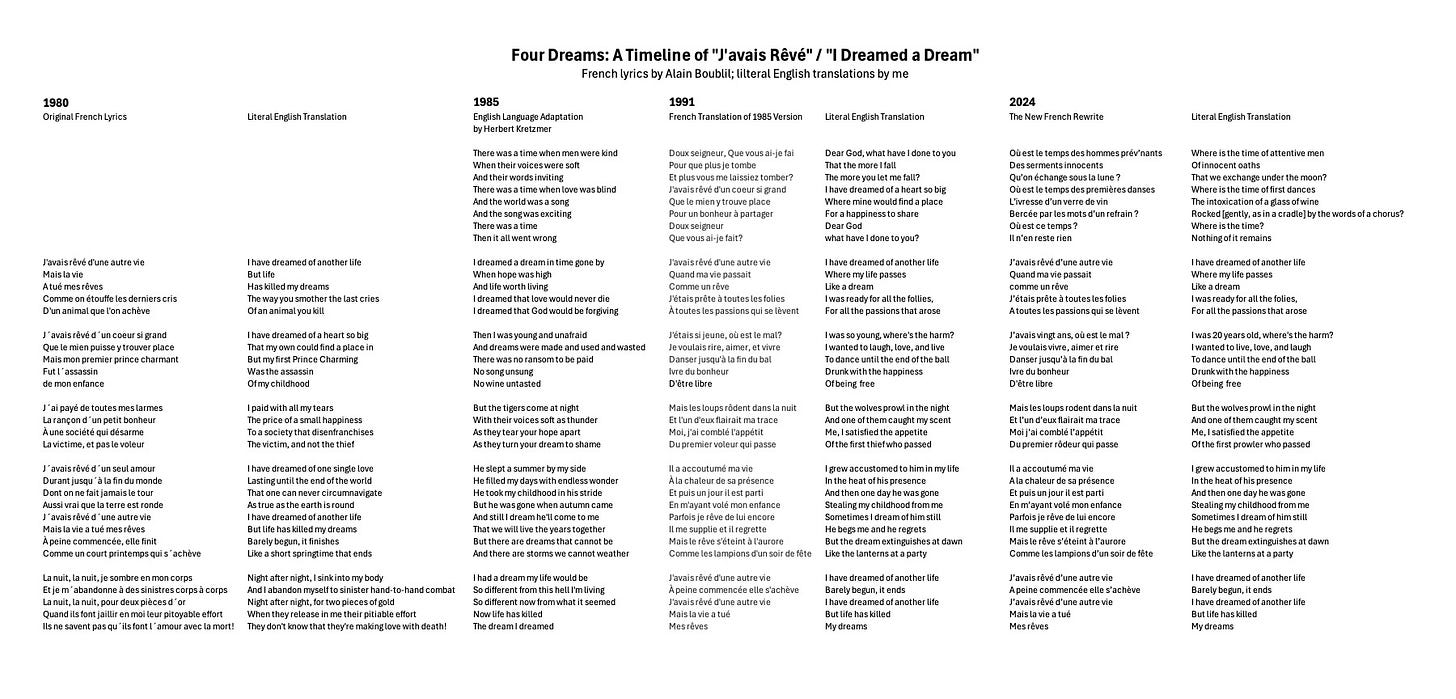

a detailed comparison of four different iterations of the song “I Dreamed a Dream” and how those changes are emblematic of the 2024 French edition,

the metrics of this new production’s success, and

why the new version stands poised to endure in France—and maybe around the world?—in the coming years.

Allons-y!

FROM HIT TO MISS TO HIT AGAIN

Here’s a thing I didn’t know until just recently: When the original, French-language Les Misérables debuted in Paris in 1980, it was a hit.

The groundwork for that initial popularity was laid with the release of a concept album of the score performed by French pop stars. Among the songs to hit the charts was “La faute à Voltaire,” sung in the show by the plucky urchin Gavroche; it was cut from the subsequent English adaptation, but it’s so well-known in France that producer Stéphane Letellier-Rampon has made sure the song was interpolated back into the show at the Châtelet.

Soon after the concept album, the show had its world premiere at Paris’ Palais des Sports, where Les Miz attracted 500,000 theatergoers across 107 performances in three months. The show only closed because the venue had another booking coming in. (This article in Le Monde has a good primer on the backstory.)

A couple of years later, Mackintosh got a hold of a recording of the French production and set about producing an English-language version. The journalist Herbert Kretzmer was enlisted to write the English adaptation, with Trevor Nunn and John Caird on board as co-directors, and a prologue sequence was added for audiences who might not know the full story of the Hugo novel as well as the French. Reviews of that 1985 production were pretty dismal, but audiences flocked and the musical soon moved from London’s Barbican to the West End (where the musical has been playing ever since). Broadway success followed, and from there Les Miz became one of the trailblazing, replica productions that helped establish the model for global touring today.

France, however, remained aloof. In 1991, a French language version of the 1985 production played Paris’ Théâtre Mogador, where it was envisioned to run as long as it had in London but closed after six months due to lackluster sales. Les Miz didn’t attempt a Paris return until 19 years later, when an international touring production came to town in 2010—in English, and right in the middle of the World Cup—and again disappointed. Not even the 2012 Oscar-winning film could excite much enthusiasm in France, where the movie ranked ninth at the national box office the week it was released.

Letellier-Rampon, the independent creative producer who’s teamed with the Châtelet on the new Les Miz, began his career as a press agent and repped that 2010 production. That was when he first met Boublil and Schönberg. Six years later, Boublil caught a performance of an original, French-language, musical adaptation of Oliver Twist that Letellier-Rampon executive produced—and its success suggested to Boublil that the producer just might be the guy to help give Les Misérables one more shot in Paris.

“I thought that if we come back to France, we must do it in French, with a French team, a French director, a French cast, and a French orchestra. And we must do it in humility,” Letellier-Rampon tells me. “We must organize things for the French to reappropriate the show and fall in love with it.”

It took a few years to convince Mackintosh to give them the rights, and a few more (with pandemic delays) to find a funder and a venue. Eventually this Les Misérables found its home at the Châtelet, the Paris institution widely credited with popularizing Broadway-style musical theater in France with its splashy, English-language productions of classic shows, plus newer work including An American in Paris, which had its pre-Broadway tryout at the Châtelet in 2015.

The Châtelet gave Les Misérables its annual holiday musical slot—which in prior years has yielded hit runs for 42nd Street and, last year, the international tour of West Side Story—and ponied up €5.3 million (~$5.6 million) for a production featuring a cast of 39, plus 40 musicians and some 300 costumes.,

Director Ladislas Chollat, who also staged Oliver Twist, took inspiration from the work of Gustav Doré (particularly from Doré’s drawings of Hell)—and from the gallons of ink Hugo must have used to write his massive tome—for a richly shadowed production in which projected splashes of ink help set the scene and spotlight the action.

The show arrives in Paris after two decades that have slowly burnished the local reputation of musical theater as an art form. In addition to the yearly programming at the Châtelet, which lent musicals a touch of snob appeal by performing them in the original language (English) as you would an opera, Stage Entertainment concurrently began to find success with local-language, replica productions of megahits like The Lion King. Just last year, the newly renovated Lido 2 Paris, a Champs-Élysées venue devoted to musicals and run by former Châtelet exec Jean-Luc Choplin, opened to add its own programming to the mix.

Combine all that with the appeal of a new production defined by French sensibilities, and Les Misérables had all the ingredients to stoke enthusiasm.

Edouard Dagher, a spokesman for the Châtelet, says the signs of success were there from the start. An early press event featuring five members of the cast performing a few songs, with no costumes or sets, drew more than 100 journalists; usually such events attract 40, tops. Le Monde gave the show an eight-page spread in its magazine, and The New York Times gave it some pre-opening international coverage.

“There was a lot of curiosity and excitement, and there was a kind of suspense in it,” Dagher says. “Everyone was asking: Will Les Misérables finally become as popular as it is everywhere else?”

Signs point to oui. Tickets are basically sold out, except for the handful of seats the theater releases daily. And reviews, for the most part, have been off the charts. “Les Misérables makes majestic comeback to Paris,” proclaims the headline of Rosita Boisseau’s review in Le Monde; she later calls it a “highly successful staging, which is both cramped and sober, evocative and eloquent.” In Le Figaro, critic Ariane Bavelier praises the “successful casting, subtle sets and intact emotion” of a production that “should become a landmark.”

One element of the production that’s been drawing plaudits is the French language adaptation, newly revised for 2024. The show, Boisseau writes, “benefits from a fine polish, notably from Boublil, who has reworked 20% of the libretto, attuning Hugolian lyricism to our everyday lives today.”

THE EVOLUTION OF “J’AVAIS RÊVÉ” / “I DREAMED A DREAM”

Those lyrical changes grew out of Boublil’s longtime desire to refine the 1991 French version, and were further shaped by the writer’s close work with director Chollat.

One of the goals, Dagher explains, was to enhance the prosody of the language, making it easier and more mellifluous to sing. The collaborators also adjusted lines to allow each character to speak “in a more authentic way, more fitting to their social condition,” Dagher continues, and to update some original language that now sounds old-fashioned.

“Alain wanted to bring the show more in correspondence with the moment we are living right now,” Letellier-Rampon says.

To get a sense of how the libretto has changed over the years, take a look at this line-by-line comparison of what is probably the show’s best-known song in English, “I Dreamed a Dream.” It’s also the tune that French journalists love to point out condenses the novel’s fifty-page saga of Fantine’s tragic backstory down to three minutes of stage time.

One thing you’ll notice is that the first verse of the most familiar version of the song—the one starting with the line “There was a time when men were kind…”—doesn’t exist until 1985. The 1980 version goes straight into “I have dreamed of another life,” and features darkly violent language (“killed,” “assassin,” “smother”) and political commentary about the injustices of “a society that disenfranchises / The victim, and not the thief.” The last verse moves into an explicit look at the character’s sex work, with a line (“They don’t know that they’re making love with death!”) that echoes a lyric in the English version’s “Lovely Ladies.”

Subsequent revisions of the song dwell less on the murderous language and instead focus on Fantine’s memories of being young and carefree, and of her dalliance with a man who left her pregnant and penniless. (Those tigers that come at night? They’re wolves in the French version.)

In 1991 the song began with a prayer, asking what she did to deserve the life that God has let her fall into. It’s a choice that lines up with the thread of religiosity that runs through Les Misêrables, but this first verse has been completely rewritten for the 2024 version. Now it more closely matches the English version, with a stronger focus on Fantine’s psychology and the prior life she longs for. It’s a more intimate take, which fits with a production that aims to tamp down some of the bombast to put the focus on the people.

BUT WILL I EVER GET A CHANCE TO SEE IT?

Quite possibly. Prospects for a future life for the production look good, and although nothing has been set, plans are in the offing to tour this Les Misérables in France in 2026, capping off with a return to the Châtelet late that year. There’s interest as well in taking the show abroad—Letellier-Rampon mentions French-speaking nations like Luxenberg, Belgium, Switzerland, and francophone Canada as possibilities, not to mention certain Asian markets that might also be receptive to a French-language tour.

In the meantime, the Châtelet will continue to embrace French-language musicals with next year’s holiday show: a new French translation of Jerry Herman and Harvey Fierstein’s 1983 musical La Cage aux Folles.

Meanwhile, Letellier-Rampon is also at work reviving his production of Oliver Twist in Paris, with a subsequent tour in Europe and Asia also being considered. He’s also got a new, French-language musical adaptation of Les Liaison Dangereuses in the works.

For now, the only certain future for the new Les Miz lies in the cast recording, already available in the Châtelet gift shop. But Letellier-Rampon is betting there’s more to come.

“There’s no reason why the show can’t succeed in France,” he says. “The audience is deeply touched by the words now. It’s really our story. It’s really inside us.”

FURTHER READING

Catch up on the local industry context in this story from January about the rise of musical theater in Paris and why it was such a long time coming: